- Home

- Jim Fergus

The Vengeance of Mothers Page 19

The Vengeance of Mothers Read online

Page 19

In addition to our duties hauling wood, the Cheyenne women have now put us to work carrying water from the creek every morning, not only for our own use but also for theirs. We have each been assigned a lodge at which we are to appear at dawn to pick up an empty pouch made from the stomach of a buffalo, which is left for us in front of the tipi. This we each carry down to the river and fill with fresh water, what the Cheyenne call “living” water as opposed to the “dead” water from the night before, the remainder of which the Cheyenne women pour on the ground outside each morning. Once filled, we carry the pouch back to the respective lodge and deposit it in front of the opening. It is cold, wet, heavy work, and there has been much speculation among us about whether or not we are being made slaves, or if they are simply giving us preparatory lessons in the wifely duties, which, conveniently, happen to benefit them, as well.

There is so much to learn about this new world, into which we try to immerse ourselves, making every effort not to judge too harshly some of the customs that seem incomprehensible to us. After all, what else is there to do? Thus we have adopted as our group motto: adapt or perish.

19 May 1876

We have been informed that a feast and a dance is to be held in our honor, this in order to formally welcome us to the village, and so that the young men can have a look at us as prospective wives. “Let us think of it as a kind of savage debutante ball,” said Lady Hall when we heard the news.

Some of the Cheyenne girls, who will also be participating in the event, are teaching us the correct steps for the first dance of the evening—a very strict, formalized style which involves a great deal of prancing synchronization of movement. There appear to be variations of this dance, with different steps, depending upon the occasion. I must say that during our first lessons, we find it repetitive and not terribly lively, and we are all hoping that the actual event will be more animated … or as Lulu puts it, “bouncier.”

“If we want something bouncier,” she said, “I will learn you all how to do the cancan. I think they never seen a real cancan before.”

“I would say that is a fair assumption, dear,” said Lady Hall.

“But it not so easy to put on a cancan without the right music,” said Lulu. “We need horns, trombones, a tuba. And the correct dresses, with petticoats, stockings, and high heels.”

“All of which, my dear Lulu, might be rather difficult to come by here in the wilderness.”

Never at a loss to edify us on a subject about which she is knowledgeable, Lady Hall continued: “For those of you who may be unfamiliar with the Parisian quadrille, or cancan as it is commonly known, allow me to enlighten you. It is, in fact, a rather risqué—considered by many, even indecent—music hall dance performed primarily by courtesans … no offense intended, Lulu …

“Indeed, my dearest companion Helen Flight and I had occasion to witness one such performance at the Alhambra Palace Music Hall on Leicester Square in the fall of 1870. A traveling troupe of women dancers from France crossed the channel to perform a ballet called, rather grandly I should say, Les Nations—The Nations; I believe they had the intention of making an international tour, which they began in Great Britain as a trial run to see how it would be received.”

“Oui, oui!” said Lulu excitedly. “But I know those girls! The star of the show, Finette, was my teacher and my best friend. It was she who learn me to dance!”

“Yes … well some of the women impersonated men,” Lady Hall went on, ignoring Lulu, “and dressed as such, while the others wore long dresses, with, as Lulu suggests, several layers of frilly petticoats, stockings, and heels. During the dance, which involved a series of lewd antics and lascivious bodily movements, those attired as women pulled up their dresses and kicked their legs as high as their heads, exposing their petticoats and drawers, in addition to just a flash of naked thigh above their high stockings. It was … well, it was scandalous.”

“How did it happen, Lady Hall,” I asked, “that you and Helen found yourselves in the audience of such a performance?”

“Ah, well you see, dear, we attended in an official … I should say semiofficial capacity,” she answered, “at the behest of our dear friend Lord Chamberlain, who was responsible for maintaining public order and decency in the city’s theatres and those of its environs. His lordship and his fellow magistrates had been receiving complaints about the sensual nature of this ballet, and he wished Helen and me to provide him with an eyewitness account. Of course, for obvious reasons, he could not attend himself, for it would hardly do for a member of the House of Lords to be seen by the public at such a spectacle. Thus Helen and I were, if you will, serving as his eyes and ears.”

“And how did you report back to your lord?” I asked.

Here Lady Hall hesitated for a moment before issuing a small, sly smile. “If you must know, Helen and I found the performance quite … exciting … exhilarating I should even say … all those lovely girls kicking up their heels so exuberantly, exposing their undergarments and the alabaster white flesh of their thighs … yes, we told Lord Chamberlain the truth … we absolutely adored it! And judging by the enthusiastic reaction of the audience, everyone else appeared to enjoy it as well. As a consequence of our report, his lordship had the police shut the show down the following night, and he sent the troupe immediately back to France. He later told us privately that if Helen and I were so enthusiastic about the performance, it could only have a dangerous effect on public morals.”

“But we French are not so bourgeois as the British, or the Americans,” said Lulu. “We are not so worried about public morals. We are not so hypocrites. Ah, oui, close the show down because all who see it have fun!” Here Lulu, being the actress that she fancies herself, assumed a deep voice of bureaucratic authority, wagging her finger sternly. ‘Ah, non, we must not allow the public to have too much fun … fun is very dangerous … très dangereux.’ But you see,” she continued in her normal voice, “everybody who watches it loves the cancan, for it is a dance of joy and liberation. If no one else wish to learn, I will dance alone for the entertainment of our Cheyenne hosts.”

Several of us could not resist a laugh at this lively girl’s spirit, always so bright and cheerful. We had come to depend upon her good humor to lift our own morale when it sagged.

“I would suggest, dear,” said Lady Hall, “that we first consult Meggie and Susie on this matter. It would not do to offend our hosts at the welcome dance.”

“If I may say so, Lady Hall,” said I, “this is just the kind of thing the twins wish for us to sort out on our own. They made themselves quite clear about that. Personally, I believe that if we avoid displaying the ‘alabaster white flesh of our thighs,’ as you so sensuously put it, a lively dance would not be considered offensive. Perhaps it might even be a good way to introduce ourselves to our hosts. Of course, no one is obligated to participate.”

“I will dance with you, Lulu,” announced timid little Hannah, who was the last girl in our group whom I could have imagined making such an offer … well, except perhaps for Lady Hall. “I love to dance, and I should like to learn the cancan.”

“As would I,” I said.

“My people love to dance,” said Maria Gálvez. “I will join … even though my thighs are brown, not white.”

“Excellent!” said Lulu. “Ah, oui, now we have a real chorus line…” She looks at us as if counting heads. “But we still have … how you say … we still have three flowers on the wall.”

“Three wallflowers, I think you wish to say, dear,” said Lady Hall. “Well, I shall not sit this dance out. I am, after all, the only other person among you, besides Lulu of course, who has actually witnessed a cancan performance. I have to admit that after having seen the spectacle, Helen and I tried a few kicks of our own at home in front of the mirror … however, the two of us were so hopelessly clumsy and got laughing so hard that we fell down on top of each other.”

“Yes, you see how much fun it is!” said Lulu. “Now we only

have Astrid and Carolyn who are still flowers on the wall.”

“My country, too, has a long tradition of folk dancing,” said Astrid. “Our major instrument of music is the fiddle, and the form of our dance is quite stylized. We, however, are well-covered, even our heads and our arms. I am afraid that the cancan might be a bit too … too French for me.”

“Ah, oui,” said Lulu, “I imagine you Norvégiens even make love dressed in winter attire … with mittens on your frosty hands.”

I should here mention that although most of us appreciate Lulu’s good-natured optimism, I do not include Astrid among our French gamine’s admirers. The two are complete opposites in both temperament and character—one gay, chatty, and always positive, the other dark, quiet, with a tendency to brood. I am quite fond of them both, but from the beginning of our journey, they have not been close, and sometimes even at odds. Astrid finds Lulu to be frivolous and vapid … and … how shall I say this politely … of questionable morals due to her former employment. While Lulu finds Astrid to be gloomy, dull, and with a disposition “like low clouds in winter,” as she puts it. I’ve wondered if the fact that Lulu comes from the sunny Mediterranean, while Astrid hails from the frozen north country, does not partly define their differing characters.

“And you, Carolyn,” said Lulu, “will you not join our chorus line?”

Carolyn, always thoughtful and with a wry sense of humor, seemed to consider the question for some time. “You know, if one of my fellow lunatics in the insane asylum had come to me six months ago,” she said with an ironic smile, “to warn me that I was to be abducted by western savages, taken to live in an Indian village in Wyoming Territory, and there asked to perform the cancan, I would have known that woman had been justly committed. Yet here we all are …

“In answer to your question, Lulu, I must tell you that in our church, dancing was strictly forbidden—it was considered to be the devil’s recreation, leading to debauchery, fornication, and adultery. Therefore, I have never had occasion to learn how. However, I did once express my mild interest in the art form to my husband, the minister, wondering idly what it would be like to dance a lively Virginia reel. He responded that if I did not put such impure thoughts out of my mind, I risked going to hell, where I would be condemned to dance for eternity in the flames with the rest of the sinners.”

“Mon Dieu!” said Lulu. “But I would much rather dance in hell than go to your church! And if you are to be sent there just for thinking about dancing, I can learn you a few steps much more interesting to take down with you.”

“Very well,” said Carolyn, “you’ve convinced me, Lulu. I shall give it a try.”

20 May 1876

Last evening several Cheyenne women, among them Chief Little Wolf’s first wife, Quiet One, his second wife, Feather on Head, and his daughter, Pretty Walker, came to our lodge and presented us with a peculiar gift—seven individual coiled pieces of thin braided rope, which when unwound revealed two long branches attached to the first length. We were pleased to find that both Feather on Head and Pretty Walker speak a good bit of English, taught them evidently by May Dodd. When it became clear to them that we had no idea what we were to do with these items, Pretty Walker demurely parted her deer hide skirt and revealed its purpose. The first length of rope encircled her waist as a kind of belt, knotted in front. The two attached branches passed down between her thighs on either side of her private parts, which themselves were covered by a kind of loin cloth. Each branch was then wrapped around her upper legs nearly to her knees.

“Brilliant!” said Lady Hall. “A primitive chastity belt. How charming.”

The Cheyenne women then went about taking what appeared to be general measurements of each of us, which process consisted of looking us over critically, spinning us around and touching us lightly here and there, with a little chattering between them, which, of course, we did not understand. Nor did we understand the exact purpose of this examination, although our actress Lulu suggested that we were being measured for costumes.

“You know, before I took up with Helen,” said Lady Hall idly, as one of the women took her measure, “—a liaison that scandalized all of British society, I might add—I was married for two years to Sir John Hall of Dorchester. In the matter of chastity, I’m afraid that my horse has long since left the barn.”

“What horse?” asked Lulu, as another woman spun her around.

“My virginity, dear. It is only an expression.”

“If m’lady doesn’t object,” said Hannah, “I would like to wear one of those strings. You see … my horse is still in the barn, and I should like to keep her there.”

“Of course you would, Hannah,” said Lady Hall. “And if you wish to be bound up like a trussed chicken, far be it from me to stand in your way.”

“My horse was stolen from the barn when I was thirteen,” said Lulu. “I have never seen it since.”

“That’s the way it is with virginity, dear. Once it leaves the barn, it never returns.”

When the Cheyenne women had finished with us, they took their leave.

We know now the purpose of their measurements, for they returned this evening, bearing the most beautiful deerskin dresses for us to wear to the dance, exquisitely embroidered with trade beads and beaver quills. The workmanship is magnificent, especially considering the short amount of time in which it has been accomplished. In addition, the dresses are wonderfully comfortable, draping over our bodies like second skins. Just trying them on, and admiring each other, made us feel a bit more as if we belong. We scarcely know how to thank them.

This evening Quiet One and Pretty Walker also brought May Dodd’s daughter, Little Bird, with them to our lodge. Also accompanying them was my friend, the Arapaho girl Pretty Nose, whom I had not seen since our arrival in the village. Little Bird, or Wren as the Kellys tell us May called her daughter, is a beautiful baby. We are all struck by the fact that she is fair of skin, with light brown hair, and blue eyes, whereas Little Wolf himself is quite dark. She clearly takes after her mother. I asked if I could hold the child, and when Pretty Walker placed her in my arms, I promptly, and without any warning whatsoever, burst into tears. The weight and warmth of her little body wrapped in a blanket brought back such vividly painful memories of my own daughter’s infancy.

Because the Cheyenne women seem so generally stoic, as, indeed, does the Arapaho girl, Pretty Nose, I was surprised when, upon my outburst, she also began to cry, turning away from us, and covering her eyes.

I gently handed Wren back to Pretty Walker, approached Pretty Nose, and took her in my arms, her body shaking as she sobbed. When finally her trembling began to subside, I took her broad brown face in my hands, her warm tears running between my fingers. She kept her gaze diverted from mine, her expression one of inconsolable heartbreak. She did not know that I had heard her story, for we had not spoken of such matters when we were riding together, both preferring to keep our respective sorrows to ourselves. Finally, she looked me directly in the eyes. In that long moment, she, too, knew everything about me, and we were bound forever in the confederacy of grieving mothers. I put my arms around her again, and she hers around me … we held each other and we wept.

21 May 1876

The night of the dance is fast approaching and we are all quite nervous about it. Increasing our trepidation, this evening we were visited by a character named Dog Woman, who is evidently in charge of organizing all important tribal social events, and whom Pretty Walker brought to our lodge. I say “character” for the Cheyenne refer to her as he’emnane’e, which translates to half-man half-woman. We frequently see Dog Woman about the village, for he/she is much in demand as a matchmaker, with special powers in all matters romantic. Sometimes dressed as a woman, and sometimes as a man, he/she is said to possess the characteristics of both sexes, which evidently earned him/her the status of holy person.

In this particular instance, Dog Woman arrived dressed as a woman. Between Pretty Walker’s English and

our more limited sign language, we came to understand that the purpose of her visit was to get a sense of which available young men might be the most suitable partners for each of us at the dance, with the goal being that these pairings will quickly lead to matrimony. It was one thing while we were traveling to idly speculate about our future as the brides of Cheyenne warriors, quite another now that the reality of the moment approached in the person of this distinctly peculiar matchmaker.

Dog Woman, whom I must say cannot be counted among the comeliest of the Cheyenne, was dressed in a white woman’s gingham dress that must have been purchased at the trading post. She looked us each up and down, touched us lightly here and there, for what purpose we did not know, grunting and muttering all the while in varying tones running the spectrum from approbation to disapproval, alternately nodding and shaking her head crankily. However, when she reached Lady Hall, the Englishwoman held up the palm of her right hand in the universal sign for “stop.”

“Do not lay hands on me, madam,” she said, in her most commanding tone of voice. “I dislike being manhandled … or womanhandled … by strangers.”

Dog Woman stared at m’lady for a moment, then smiled and nodded her head with a certain self-satisfaction, as if she had come to some important conclusion. Then she moved on to her cursory examination of the next one of us.

We have begun rehearsals for the cancan performance, our largely preposterous efforts thus far providing a bit of comedy to leaven our anxiety, while at the same time increasing it. As we laugh at ourselves and at each other, we do so fully aware that we risk becoming a laughingstock for all at the dance. Even the irrepressibly optimistic Lulu, our sole “professional,” is beginning to express grave misgivings regarding the negligible … dare I say, nonexistent talents of her thoroughly amateur troupe. “Mes chères filles,” she said, shaking her head sadly during our first rehearsal, “my darling girls, but that is no cancan you dance; that is old ladies shuffling along in the park with their canes. Can you not make your kicks more higher, more energetic than that? You must point your toes to the heavens. My teacher Finette always say, ‘Imagine that you kick the stars from the sky.’”

La Vengeance des mères

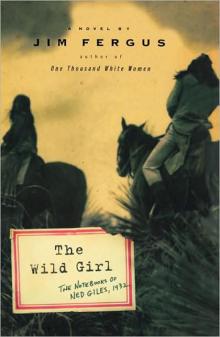

La Vengeance des mères The Wild Girl: The Notebooks of Ned Giles, 1932

The Wild Girl: The Notebooks of Ned Giles, 1932 One Thousand White Women

One Thousand White Women One Thousand White Women: The Journals of May Dodd

One Thousand White Women: The Journals of May Dodd Chrysis

Chrysis Strongheart: The Lost Journals of May Dodd and Molly McGill

Strongheart: The Lost Journals of May Dodd and Molly McGill The Vengeance of Mothers

The Vengeance of Mothers The Wild Girl

The Wild Girl