- Home

- Jim Fergus

One Thousand White Women: The Journals of May Dodd

One Thousand White Women: The Journals of May Dodd Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Epigraph

INTRODUCTION

PROLOGUE

THE JOURNALS OF MAY DODD

NOTEBOOK I - A Train Bound for Glory

23 March 1875

24 March 1875

27 March 1875

31 March 1875

3 April 1875

8 April 1875—Fort Sidney, Nebraska Territory

11 April 1875

NOTEBOOK II - Passage to the Wilderness

13 April 1875

13 April 1875

17 April 1875

18 April 1875

19 April 1875

20 April 1875

21 April 1875

22 April 1875

23 April 1875

24 April 1875

25 April 1875

5 May 1875

6 May 1875

7 May 1875

8 May 1875

NOTEBOOK III - My Life as an Indian Squaw

12 May 1875

14 May 1875

15 May 1875

18 May 1875

19 May 1875

21 May 1875

22 May 1875

NOTEBOOK IV - The Devil Whiskey

23 May 1875

26 May 1875

28 May 1875

3 June 1875

1 June 1875

4 June 1875

5 June 1875

7 June 1875

15 June 1875

17 June 1875

NOTEBOOK V - A Gypsy’s Life

7 July 1875

14 July 1875

1 August 1875

7 August 1875

8 August 1875

9 August 1875

11 August 1875

20 August 1875

23 August 1875

28 August 1875

6 September 1875

10 September 1875

14 September 1875

NOTEBOOK VI - The Bony Bosom of Civilization

14 September 1875, Fort Laramie (continued)

18 September 1875

19 September 1875

20 September 1875

22 September 1875

23 September 1875

28 September 1875

3 October 1875

5 October 1875

8 October 1875

10 October 1875

14 October 1875

18 October 1875

NOTEBOOK VII - Winter

1 November 1875

5 November 1875

10 November 1875

10 December 1875

12 December 1875

18 December 1875

25 December 1875

23 January 1876

26 January 1876

28 January 1876

29 January 1876

30 January 1876

17 February 1876

22 February 1876

24 February 1876

28 February 1876

1 March 1876

CODICIL

EPILOGUE

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Praise

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

Copyright Page

To Dillon

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Writing careers in general, and the writing of novels in particular, can be accurately, if somewhat unromantically, likened to rolling large boulders uphill. Sometimes the writer needs a little help, and if we’re very lucky, people come along at opportune moments and not only offer a word of encouragement, but actually put their shoulder to the boulder and help us to move it forward. I have been that lucky, and owe thanks to many people—friends, family, and colleagues—for the existence of this book. So special and grateful thanks to all of the following:

To Barney Downhill, without whose faith and generosity I couldn’t have been a writer. To my agent Al Zuckerman, the quintessential pro, whose unfailing instincts culled this story out of the rockpile. To my editor, Jennifer Enderlin, for her constant enthusiasm for this project, her hard work, good cheer, and impeccable editorial judgment. To Laton McCartney, for years of wise council and boundless optimism. To Jon Williams, whose early turn at this particular boulder encouraged me to continue pushing. To Bob Wallace, who gave me my first magazine assignment almost twenty years ago, and, remarkably, stepped back into my professional life once again as editor in chief just in time to oversee this much-belated “first” novel. To Bonny Hawley and Douglas Tate, for invaluable insights and information on British place, name, and character. To Laurie Morrow, for her precise woman’s perspective on the subject of romantic attraction. To Rev. Rolland W. Hoverstock, for critical information about the Episcopal church and ceremonies circa 1875. To Sister Thérèse de la Valdène, for providing always cherished retreats at Dogwood Farms, and to Guy de la Valdène, for wonderful dinners and a large vote of confidence when it was most needed. Finally, thanks to Dillon for cheerfully occupying over the past fifteen years the nearly always thankless role of writer’s spouse.

While the author acknowledges the help and support of all of the above people in the creation of this novel, he accepts full responsibilities for any of its shortcomings.

Five percent of the author’s royalties earned on the sale of One Thousand White Women will be donated to the St. Labre Indian School, Ashland, Montana 59004.

Women will love her, that she is a woman

More worth than any man; men that she is

The rarest of all women.

—William Shakespeare,

The Winter’s Tale V, 1

INTRODUCTION

by J. Will Dodd

As a child growing up in Chicago, I used to scare my kid brother, Jimmy, silly at night telling him stories about our mad ancestor, May Dodd, who lived in an insane asylum and ran off to live with Indians—at least that was the fertile, if somewhat vague, raw material of secret family legend.

We lived on Lake Shore Drive and our family was still quite wealthy in those days, descendants of “old” money—a fortune and a dynasty begun by our great-great-grandfather, J. Hamilton Dodd, who as a young man in the mid-nineteenth century began plowing up the vast Midwestern prairies around Chicago in order to cultivate grain in what was some of the most fertile farmland in the world. “Papa,” as he is still known by his descendants, was one of the original founders of the Chicago Board of Trade; he was friend, crony, business partner, and competitor, as the case might be, of all the most prominent entrepreneurs in that booming Midwestern metropolis—among them Cyrus McCormick, inventor of the reaper, Philip Armour and Gustavus Swift, the famous pork and beef packers, and the brothers Charles and Nathan Mears, lumbermen who bought up and single-handedly destroyed the great old-growth white pine forests of Michigan.

No one in our family spoke much about my great-grandmother May Dodd. Among the wealthy, ancestral insanity has always been a source of deep-rooted embarrassment. Even these many generations later, when the razor-sharp robber-baron genes have been largely blunted by line-breeding and soft country-club living, by boarding school and Ivy League educations, even now no one in our social milieu likes to admit to being directly descended from a crazy woman. In the heavily edited official family history, May Dodd remains little more than a footnote: “Born March 23, 1850 … second daughter of J. Hamilton and Hortense Dodd. Hospitalized at age 23 for a nervous disorder. Died in hospital, February 17, 1876.” That’s it.

But even old-money taciturnity—for which there is no competition on earth—and the equally unparalleled ability of the rich to keep dark secrets, could not completely obscure the whispered rumors that trickled

down through the generations that May Dodd had actually died under somewhat mysterious circumstances—not in the hospital as officially stated, but somewhere out West. This was the story that fueled my and my brother Jimmy’s imaginations.

By the time I was a junior in college, our father had squandered most of the family fortune, which had by then already been vastly diluted by a couple of generations of unproductive heirs—what people used to call “wastrels.” Pop finished it off with a series of bad investments in Chicago commercial real estate just when that market was collapsing, and then he managed to break a trust and drink away the last bit of money that was to pay for his sons’ higher education. Partly as a result of this Jimmy got drafted—which was almost unheard of in our circles—and sent to Vietnam, where he was killed when he stepped on a land mine in a rice paddy in the Mekong Delta. Less than six months later, Pop drank himself to death.

I was luckier than my brother and managed to stay in college, drew a high lottery number, and graduated with a degree in journalism, armed with which I eventually became the editor in chief of the city magazine Chitown.

It was while researching a piece for the magazine about the old scions of Chicago that I happened to come again across May Dodd’s name. I remembered the tales that I used to tell Jimmy, and I wondered where I had first heard the rumor that she had gone “out West to live with Indians—which in our family had become a kind of euphemism for insanity.

I started poking around in the family archives, casually at first, then with greater and greater interest—some might even say obsession. One letter, reportedly written by May Dodd from inside the asylum to her children, Hortense and William, who were just infants at the time of her incarceration, had survived. Source of both the old family rumor, as well as proof positive of how crazy May really was, this letter was for me the beginning of a long, strange journey.

I took a leave of absence from my job at the magazine in order to devote myself full-time to following the convoluted trail of May Dodd’s life. My research led me eventually to the Tongue River Indian reservation in south-eastern Montana. It was here, armed with my family letter as proof of my ancestry, that I was finally granted access to the following journals, which have remained among the Cheyennes—a sacred tribal treasure for well over a hundred years. I need hardly add that the tale they tell of U.S. government intrigue cum social experiment has also remained one of the best-kept secrets in Western American history.

The following prologue to the journals briefly describes the historical events that led to May Dodd’s story, and is based on several sources, including newspaper accounts of the time, the Congressional Record, the Annual Report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, correspondence from the files of the Adjutant General’s Office in the National Archives in Washington, D.C., as well as various materials available in Chicago’s Newberry Library. The Indian point of view pertaining to Little Wolf’s visit to Washington in 1874, and the subsequent chain of events is based on Northern Cheyenne oral history recounted to me by Harold Wild Plums in Lame Elk, Montana, in October 1996.

PROLOGUE

In September of 1874, the great Cheyenne “Sweet Medicine Chief” Little Wolf made the long overland journey to Washington, D.C., with a delegation of his tribesmen for the express purpose of making a lasting peace with the whites. Having spent the weeks prior to his trip smoking and softly discussing various peace initiatives with his tribal council of forty-four chiefs, Little Wolf came to the nation’s capital with a somewhat novel, though from the Cheyenne worldview, perfectly rational plan that would ensure a safe and prosperous future for his greatly beseiged people.

The Indian leader was received in Washington with all the pomp and circumstance accorded to the visiting head of state of a foreign land. At a formal ceremony in the Capitol building with President Ulysses S. Grant, and members of a specially appointed congressional commission, Little Wolf was presented with the Presidential Peace Medal—a large ornate silver medallion—that the Chief, with no intentional irony, a thing unknown to the Cheyennes, would later wear in battle against the U.S. Army in the Cheyennes’ final desperate days as a free people. Grant’s profile appeared on one side of the medal, ringed by the words: LET US HAVE PEACE LIBERTY JUSTICE AND EQUALITY; on the other side an open Bible lay atop a rake, a plow, an ax, a shovel, and sundry other farming implements with the words: ON EARTH PEACE GOOD WILL TOWARD MEN 1874.

Also in attendance on this historic occasion were the President’s wife, Julia, who had begged her husband to be allowed to attend so that she might see the Indians in all their savage regalia, and a few favored members of the Washington press corps. The date was September 18, 1874.

Old daguerreotype photographs of the assembly show the Cheyennes dressed in their finest ceremonial attire—ornately beaded moccasins; hide leggings from the fringe of which dangled chattering elk teeth; deerskin war shirts, trimmed at the seams with the scalps of enemies and elaborately ornamented with beads and dyed porcupine quills. They wore hammered silver coins in their hair, and brass-wire and otter-fur bands in their braids. Washingtonians had never seen anything quite like it.

Although over fifty years old by this time, Little Wolf looked at least a decade younger than his age. He was lean and sinewy, with aquiline nose and flared nostrils, high, ruddy cheekbones, and burnished bronze skin that bore the deep pockmarks of a smallpox epidemic that had ravaged the Cheyenne tribe in 1865. The Chief was not a large man, but he carried himself with great bearing—head held high, an expression of innate fierceness and defiance on his face. His demeanor would later be characterized by newspaper accounts as “haughty” and “insolent.”

Expressing himself through an interpreter by the name of Amos Chapman from Fort Supply, Kansas, Little Wolf came directly to the point. “It is the Cheyenne way that all children who enter this world belong to their mother’s tribe,” he began, addressing the President of the United States, though he did not look directly in Grant’s eyes as this was considered bad manners among his people. “My father was Arapaho and my mother Cheyenne. Thus I was raised by my mother’s people, and I am Cheyenne. But I have always been free to come and go among the Arapaho, and in this way I learned also their way of life. This, we believe, is a good thing.” At this point in his address, Little Wolf would ordinarily have puffed on his pipe, giving all those present a chance to consider what he had thus far said. However, with usual white man bad manners, the Great White Father had neglected to provide a pipe at this important gathering.

The Chief continued: “The People [The Cheyennes referred to themselves simply as Tsitsistas—the People] are a small tribe, smaller than either the Sioux or the Arapaho; we have never been numerous because we understand that the earth can only carry a certain number of the People, just as it can only carry a certain number of the bears, the wolves, the elks, the pronghorns, and all the rest of the animals. For if there are too many of any animal, this animal starves until there is the right number again. We would rather be few in number and have enough for everyone to eat, than be too many and all starve. Because of the sickness you have brought us (here Little Wolf touched his pockmarked cheek), and the war you have waged upon us (here he touched his breast; he had been wounded numerous times in battle), we are now even fewer. Soon the People will disappear altogether, as the buffalo in our country disappear. I am the Sweet Medicine Chief. My duty is to see that my People survive. To do this we must enter the white man’s world—our children must become members of your tribe. Therefore we ask the Great Father for the gift of one thousand white women as wives, to teach us and our children the new life that must be lived when the buffalo are gone.”

Now a collective gasp rose from the room, peppered with scattered exclamations of astonishment. To interrupt a man while he was speaking, except to utter soft murmurs of approbation, was an act of gross impoliteness to the Cheyennes, and this outburst angered Little Wolf. But the Chief knew that white people did not know how to behave, and he was not surprised

. Still, he paused for a moment to let the crowd settle and to allow his chiefly displeasure to be registered by all present.

“In this way,” Little Wolf continued, “our warriors will plant the Cheyenne seed into the bellies of your white women. Our seed will sprout and grow inside their wombs, and the next generation of Cheyenne children will be born into your tribe, with the full privileges attendant to that position.”

At exactly this point in Little Wolf’s address, President Grant’s wife, Julia, fainted dead away on the floor, swooned right from her chair with a long, gurgling sigh like the death rattle of a lung-shot buffalo cow. (It was unseasonably hot in the room that day, and in her memoirs, Julia Dent Grant would maintain that the heat, not moral squeamishness at the idea of the savages breeding with white girls, had caused her to faint.)

As aides rushed to the First Lady’s side, the President, reddening in the face, began to rise unsteadily to his feet. Little Wolf recognized that Grant was drunk and, considering the solemnity of the occasion, the Chief felt that this constituted a fairly serious breach of etiquette.

“For your gift of one thousand white women,” Little Wolf continued in a stern, louder voice over the rising clamor (although at this point interpreter Chapman was practically whispering), “we will give you one thousand horses. Five hundred wild horses and five hundred horses already broke.”

Now Little Wolf raised his hand as if in papal benediction, concluding his speech with immense dignity and bearing. “From this day forward the blood of our people shall be forever joined.”

But by then all hell had broken loose in the room and hardly anyone heard the great leader’s final remarks. Senators blustered and pounded the table. “Arrest the heathens!” someone called out, and the row of soldiers flanking the hall fell into formation, bayonets at the ready position. In response, the Cheyenne chiefs all stood up in unison, instinctively drawing knives and forming a circle, shoulders touching, in the way that a bevy of quail beds down at night to protect itself from predators.

La Vengeance des mères

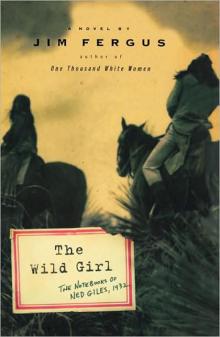

La Vengeance des mères The Wild Girl: The Notebooks of Ned Giles, 1932

The Wild Girl: The Notebooks of Ned Giles, 1932 One Thousand White Women

One Thousand White Women One Thousand White Women: The Journals of May Dodd

One Thousand White Women: The Journals of May Dodd Chrysis

Chrysis Strongheart: The Lost Journals of May Dodd and Molly McGill

Strongheart: The Lost Journals of May Dodd and Molly McGill The Vengeance of Mothers

The Vengeance of Mothers The Wild Girl

The Wild Girl