- Home

- Jim Fergus

Strongheart: The Lost Journals of May Dodd and Molly McGill

Strongheart: The Lost Journals of May Dodd and Molly McGill Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Larry Yoder

In olden times, the earth thundered with the pounding of horses’ hooves. In that long ago age, women would saddle their horses, grab their lances, and ride forth with their men folk to meet the enemy in battle on the steppes. The women of that time could cut out an enemy’s heart with their swift, sharp swords. Yet they also comforted their men and harbored great love in their hearts …

—Caucasus tradition, Nart Saga 26

Archaic Greeks had heard about people ranging over the Black Sea-steppes region, a warrior society that exhibited a remarkable degree of sexual equality. Their non-Greek name, sounding something like “amazon,” was adapted to the epic form of ethnonyms, thus Amazones. The descriptive epithet antianeirai was added to call out the most notable feature of this group: gender equality. The epithet was feminine to emphasize the extraordinary status of women among this particular people, relative to the status of women in Greek culture. Unlike most other ethnic groups familiar to the Greeks, in which men were the most significant members, among Amazones it was the women who stood out.

—THE AMAZONS:

Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World by Adrienne Mayor

Everything that can be imagined is real.

—Pablo Picasso

PROLOGUE

by JW Dodd, III

Editor in Chief, Chitown Magazine

June 2019

For the benefit of new readers of this magazine, a short explanation is in order here. This is the third and final installment of the One Thousand White Women series. The first installment was published more than twenty years ago by my late father, J. Will Dodd, the founding publisher and editor-in-chief of Chitown magazine, under the title The Journals of May Dodd, written by our ancestor of that name in 1875–76. Upon my dad’s sudden death, I, JW Dodd, took over his dual positions on the masthead.

Shortly after I began my tenure as editor-in-chief, a young Cheyenne Indian woman by the name of Molly Standing Bear came to my office bearing a second bundle of journals, one that I myself edited and published here in serial form under the title The Journals of Margaret Kelly and Molly McGill. Those readers familiar with the magazine and that second installment may remember that the final journal entry ended rather abruptly, and without any particular resolution. This was not an editorial decision for the purpose of leaving readers hanging on the cliff (although that, ironically, is precisely where they were left, as I was reminded in numerous irritated letters to the editor), but simply because Molly Standing Bear, for justifiable reasons, did not entirely trust me and had withheld the remaining journals in her possession.

Although I had only been running the magazine for this short time, after a long and harrowing night of reading the journals, I decided on impulse to take a kind of unofficial leave of absence. To this end, from a storage barn on our family farm in Libertyville, Illinois, I resurrected my father’s beat-up old 1972 Airstream trailer and the 1979 GMC Suburban with which he pulled it on our summer trips to Indian country when I was a boy. After roughly ten days of cleaning and trips to my mechanic doing our best to make both of these decrepit vehicles at least minimally functional and roadworthy again, I set out from Chicago for the Tongue River Indian Reservation in southeastern Montana. My ostensible reason for this flight west was to try to convince Molly Standing Bear to allow me to publish the rest of the story. But as I drove, entering the Great Plains under a vast sky and distant horizons, offering liberation from the constraints of the city, I realized that in a sense I was also paying homage to my father, and to my own childhood. We had lost my mother to cancer when I was seven years old and those summer excursions began shortly thereafter, and were to become the happiest times of my life with Dad. He was a western history buff, specializing in the study of the Plains Indian tribes, and so our trips west always had a professional purpose, which made me feel importantly grown-up, for I was his assistant.

* * *

Finally, as readers both new and old will discover in the following pages, in order to secure the rights to Molly Standing Bear’s story, I was required to make certain concessions, chief among them to allow this mysterious young woman to serve as editor and annotator of the final installment of her tale without any editorial interference—hardly an easy decision for me, as it went against all my training and instincts. In addition, I must confess that certain revelations herein regarding my personal and professional behavior are frankly embarrassing. Still, I made a deal with Molly Standing Bear and in this spirit, I turn this series over to her.

The following journals are here reprinted with the exclusive permission of Chitown magazine.

Introduction

by Molly Standing Bear

I’ve decided I’m not giving the rest of this story to the white-man editor JW Dodd, after all. It belongs to me, to my family, to the People, and especially to the Stronghearts, and no one can tell it better than I. You see, first they invaded our country, sent their army to massacre us, stole our land, our way of life, our culture. To facilitate that process, they destroyed our livelihood by killing off our brothers, the buffalo, over thirty million of whom once populated these vast plains of grass. By the time the white man’s extermination was complete, their numbers had been reduced to a few hundred left in Yellowstone Park, and those few of us who had survived the wars had been confined on reservations, which we were not allowed to leave.

They stole our children, and with them our language, sent them to schools run by priests, cut their hair short, beat them if they spoke their own tongue, and abused them in ways unknown and unimaginable to the People. And then, as if that wasn’t enough, they stole our history and our stories, twisted and perverted them to hide the shame of their own behavior, to absolve them of guilt for their insatiable greed, their insatiable need to acquire. Does this sound like the America you know? No? Well, I didn’t think so. But it is the one we know.

It’s not that I have anything against JW Dodd. Quite the contrary, I like the man, and I remember having a little yearning for him way back when I was a kid on the res. We Indian girls didn’t meet many white boys in those days, and if we did it wasn’t the kind of encounter you’d want to have … in fact, JW was the first white boy I ever liked, and he liked me, too. He used to come out in the summertime with his dad, who went by the name of Will Dodd, a direct descendant of May Dodd. As white men go, Will Dodd was well liked and respected on the reservation, for the simple reason that he was a gentleman and honest, and he treated us with respect and consideration.

A few years back, I took another piece of the story to JW at his office in Chicago. Upon the sudden death of his father he was now running the magazine. I delivered it in my persona as a Strongheart warrior woman—beaded buckskin shift, leather leggings and moc

casins, my hair in braids wrapped in rawhide straps with beads and small bones tied into them, knife and scalp belt around my waist, from which dangled real human scalps … white-man scalps. You see, I am a shape-shifter, I have the ability to assume different forms, which I inherited from one side of my family. Now let me state right here that I really couldn’t care less if you believe this or not, and I’m not going to waste our time here trying to convince you one way or the other. I am just telling my story, our story, and maybe you will come to believe it … or not … that I leave entirely up to you.

On that day in Chicago, I was met at the front desk of the magazine by an insipid little white-girl receptionist named Chloe … I think … or another of those currently popular white-girl names. I have to say that I am a fierce-looking woman, especially in my Strongheart incarnation, and the receptionist looked me up and down with an expression that shifted between nervousness, disdain, and a kind of superior amusement. I was carrying a pair of old leather saddlebags over my shoulder that had belonged to one of the 7th cavalry soldiers killed on June 25, 1876, at the Battle of Greasy Grass, or, as the white men call it, the Battle of the Little Bighorn, or Custer’s Last Stand. The saddlebags had been taken off the dead horse of the dead soldier, a boy named Miller, by one of my ancestors, the white woman Molly McGill Hawk, who had married into our tribe, and they had been passed down by the generations of women until finally arriving in my possession.

“May I help you?” asked the receptionist, Chloe.

“I’d like to see your publisher, JW Dodd.”

“And whom may I tell Mr. Dodd is asking to see him?”

“None of your business,” I answered. “Just tell him we know each other, and that I have something that will interest him.”

This took her aback for a moment, and I could tell she was more than a little afraid of me now. “Would you mind taking a seat?” she asked, “and I’ll ask Mr. Dodd to come out.”

“Yes, I would mind. I’ll wait right here.”

“Since you got through security downstairs,” she said, looking again at my attire, “may I assume you aren’t carrying anything dangerous in those bags?”

“You may assume that,” I answered, “but I suppose that depends on what your definition of ‘dangerous’ is.”

Now she pecked something out on her cell phone, which shortly thereafter sounded a tone. This exchange of pecking and tones went on three or four more times.

When JW Dodd finally came out it was obvious he didn’t recognize me. He regarded me with an expression of surprise and curiosity, but without judgment … I’ll give him that. He led me to his office past a series of glass cubicles in which other workers appeared to be pecking things out on their various devices. They all looked up to watch me pass. I looked back at each of them with my best Strongheart, don’t-fuck-with-me gaze, and when I did they were forced to cast their eyes away from its ferocity.

JW indicated that I sit in the chair in front of his desk, and took his own behind it. “My receptionist tells me that you mentioned we know each other,” he said. “I’m sorry, but I’m afraid I don’t recognize you.”

“We met some years ago on the Tongue River Indian Reservation,” I answered. “I didn’t expect you to remember me. We were just kids. You invited me to go to the movies at the res community center.”

He laughed, suddenly remembering. “Of course, how could I forget? I had just turned thirteen years old, and you were the first girl I ever asked out on a date. I was walking from my dad’s trailer, where we parked on the res, to pick you up at your house, when a group of Cheyenne boys waylaid me and beat the crap out of me. You’re Molly Standing Bear, all grown up.”

“That’s right,” I said. “For a white boy to ask an Indian girl to the movies was overstepping tribal boundaries.”

“Yeah, I got that part.”

I remember that young JW came to my house anyway that day, all beat up and bleeding, his new jeans and the fresh white, white-boy button-down shirt he put on for the movies dirty, torn, and stained with his blood. I kind of admired him for coming like that. It showed a certain strength of character and tenacity on his part. But my mother wouldn’t let me go to the door, and I watched from the window as she sent him away. That was the last time I saw him.

Because we had trusted his father, I left those saddlebags with JW Dodd that day in his office. They contained the journals of Meggie Kelly and Molly McGill, which as his father had done with May Dodd’s journals, and after I gave him permission, he would later publish in serial form in Chitown magazine.

I could tell that day that JW still liked me; I knew he had been well educated by his dad in the history of the Plains Indians, at least the white man’s version of our history. I have to give some credit to his father, Will, for he put in the time to get to know some of the elders, who still had the old oral stories in their heads. And just maybe it was my outfit that attracted JW, too, being authentic, my savage look maybe triggering a white boy’s fantasy of seducing the Indian girl. He asked me if I still wanted to have that movie date, or maybe dinner, now that we were grown-ups, but I shut him down. I let him know this was a business call, not personal.

A few weeks later, JW showed up on the res, driving his dad’s beat-up old Suburban, and pulling the vintage Airstream trailer they always stayed in when they came out here. Both the truck and the trailer looked like they had been parked and forgotten somewhere for a couple of decades. He didn’t know it, but I was watching as he pulled up in front of tribal headquarters and stepped out of the vehicle.

It was a Saturday and only one woman was in the office, a Southern Cheyenne girl who had just recently come up from the res in Oklahoma. She was working on the weekend in order to familiarize herself with her new job. We didn’t know each other yet, but I found out later that JW asked her where he could find me, and when she tried to look me up on their website, she found that I was not enrolled as a tribal member. The only records of me she was able to find in the digital archives were a twenty-year-old police report about domestic abuse, and my obituary.

After his inquiry at headquarters, JW drove his rig to a pull-off along the river outside town, the same place he and his dad used to camp, but these days a favorite spot for alcohol and drug users to party at night, especially on a Saturday. Of course, I knew of all his movements almost before he did because the res is small and not exactly a popular vacation destination for whites, who rarely spend the night there unless stranded by weather or car trouble. Word travels fast and it is ingrained in the tribal DNA to be suspicious of any white man who comes to town asking questions, looking for someone, and pitching camp for the night.

Just after dark, I walked down the river bottom from town to see JW. Before I approached his trailer, I hung back in the shadows for a moment and watched as he was being harassed outside his door by three Indians I knew to be meth heads. Hanging out by a pickup truck nearby in which they must have arrived were four more men and five women. I had to laugh because two of those at JW’s door had been among the boys who beat him up when they were kids. They were threatening now to kick his ass unless he gave them his money and whatever alcohol he had in the trailer. I liked that he didn’t seem afraid of them. He said he’d give them what he had, and he turned to go into his trailer to get it, when they called him a chickenshit. He stopped and turned back to them. “You know, I count seven of you altogether,” he said, looking over at the others who were watching and snickering at the white man interloper, “and just one of me … so yeah, I guess maybe I am a chickenshit, or else maybe I’m just not stupid and don’t want to get my ass kicked tonight.”

I walked up then out of the darkness. “What about if it were only seven against two, white boy?” I said. “Would you be a little stupid then, and risk getting your ass kicked?”

I spoke sharply then to the men in Cheyenne, but they were already scattering like a covey of flushed prairie grouse at my arrival. They loaded their beer back into the vehicle, and th

e whole group piled into the pickup and sped off, their tires spinning in the sandy dirt.

“Yeah, if you were the second one on my side, Molly Standing Bear,” said JW, as he watched them go. “I could get real stupid. But just out of curiosity, why are they so afraid of you?”

“I scare the shit out of the brave warriors here because when I appear like this they think I’m a spirit being.”

“I don’t believe in spirit beings,” he said, “but I read a police report and your obituary today at tribal headquarters. It said you were the victim of domestic abuse, and that you died from injuries sustained. That was in January of 1997, a few months after my dad and I were here. There was a photo of you in the reservation newspaper. You were twelve years old.”

“Are you going to be polite and invite me into your tipi, or not?”

“Of course,” he said, opening the door, standing aside, and holding his arm out for me to enter. “But that’s not an answer.”

“You didn’t ask a question.” I stepped into the trailer.

“OK, so what is that all about? You look as alive to me now as you did in Chicago, so being the canny investigative journalist I am, I assume some kind of mistake was made in the newspaper.”

“That is something I can’t talk about, so please don’t ask me again.”

After we were settled on the narrow fold-out couch in the trailer, which also served as a bed, I asked him why he had come here.

“To return the journals you left with me,” he answered. “I have to tell you, Molly, I made copies of them, which I haven’t let anyone else at the magazine read yet. I wanted to ask you first for your permission to publish these in serial form. If so, you’ll have to sign a release. I assume that’s why you brought them to me. If not, I promise I’ll shred the copies.”

La Vengeance des mères

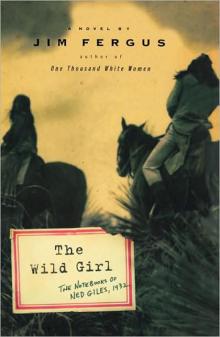

La Vengeance des mères The Wild Girl: The Notebooks of Ned Giles, 1932

The Wild Girl: The Notebooks of Ned Giles, 1932 One Thousand White Women

One Thousand White Women One Thousand White Women: The Journals of May Dodd

One Thousand White Women: The Journals of May Dodd Chrysis

Chrysis Strongheart: The Lost Journals of May Dodd and Molly McGill

Strongheart: The Lost Journals of May Dodd and Molly McGill The Vengeance of Mothers

The Vengeance of Mothers The Wild Girl

The Wild Girl