- Home

- Jim Fergus

The Vengeance of Mothers Page 14

The Vengeance of Mothers Read online

Page 14

Finally, this morning as we were riding, Lady Hall asked: “Martha, do tell us, please, have you given your splendid little donkey a name?”

And to our great surprise, and delight, for the very first time, Martha spoke: “Dapple.”

“I say! Dapple!” said Lady Hall with gusto. “A grand name for the little fellow! I presume this is a literary allusion, for if memory serves me well, Dapple is the name of Sancho Panza’s donkey in Don Quixote. Am I not correct about this, Martha?”

But for now this single word was all we would have from Martha. Still, it filled us with hope that she might yet return to us.

A final disturbing word about the donkey, Dapple … he has one annoying and potentially dangerous habit that is evidently ingrained in his species. Once or twice a day, and for no discernable reason, he raises his head and lets loose with a piercing bray that surely carries for miles across the plains. Lady Hall, who is quite knowledgeable about all matters equine, tells us that before they were domesticated and spread around the world as beasts of burden, the wild ass was originally indigenous to India. She said that unlike wild horses, donkeys do not travel in herds, but rather are solitary creatures, and that the males developed this loud bray in order to announce themselves across large distances to potential mates for breeding purposes.

This morning while we were traveling, one of the scouts rode in to tell Hawk that they had come upon a detachment of Army cavalry not far away. Hawk, in turn, rode back to impart this news to Meggie and Susie, telling them that in order to avoid the soldiers, we were swinging a wide berth that would take us some distance away from our intended route. Just then, Dapple let loose with one of his brays, and from some indeterminate distance and direction, another donkey, presumably a beast of burden traveling with the soldiers’ pack train, answered him. Hawk spoke angrily to the Kellys, and they responded in kind, entering into an aggressive argument with him. The rest of us had no idea exactly what was being said, except that the subject was clearly Martha’s donkey, toward whom Hawk kept gesturing.

Lady Hall and I rode up beside them. “I say, ladies, and gentleman, what seems to be the trouble here?”

“He wants to kill the donkey,” said Meggie. “He says it will give us away. As always, the soldiers are travelin’ with Indian scouts, who will discover us now in short order.”

“Well, sir,” said Lady Hall, “you see, that is quite out of the question. That would kill our dear Martha. Hasn’t the poor girl suffered enough?”

“Aye, exactly what me and Meggie are tryin’ to tell him,” said Susie. “We say if he harms the donkey, he’ll have us to deal with, and he’d best be prepared to slit our throats, too.”

“Well done, ladies,” said Lady Hall. “And sir, you will have me to get past, as well. Believe me, between us, we shall be formidable opponents. Have you perhaps heard of the three Furies of Greek mythology?… ah, no, I expect not…”

Ignoring Lady Hall, Hawk reined his horse to move past them, clearly intending to make good on his threat.

From my saddlebag, I pulled Seminole’s Colt .45, cocked it, and pointed it at him. He brought his horse up short in front of mine. “Leave the donkey alone, Hawk,” I said. “The girl has been through hell. That animal is all she has. We can’t let you destroy her. If you are so worried about the scouts finding us, let us stop talking about this, and get moving again.”

Hawk looked at me with a quizzical expression, as if trying to sort out whether or not I would actually shoot him over a donkey. Then he did something strange … he broke into a wide smile, shook his head with a certain incredulity … and he laughed—the first time I’d ever heard him laugh. He reined his horse in a tight circle, touched its flanks with his moccasined heels, and galloped back to the front of our loose assemblage.

“Jaysus Christ, girl,” said Meggie, astonished. “Were you really going to shoot him?”

“Of course not,” I answered. “And he knew perfectly well I wasn’t. That’s why he laughed.”

“Well, then,” said Susie, “ain’t it pleasin’ to know that Hawk has a sense of humor. Wouldn’t a’ been in the least bit amusin’ if he had killed that donkey … not to mention me, Meggie, and Lady Hall.”

We watched as Hawk conferred a moment with Red Fox, who peeled off to resume his scouting duties. Then he turned us to the southwest and we moved out at as fast a pace as we could travel. Meggie, Susie, Lady Hall, and I all broke into a light canter, and the rest of the girls, who have all by now achieved varying degrees of competence in the saddle, followed suit behind us.

We rode hard for several hours, alternately walking, trotting, cantering, and making only brief stops to water the horses. Red Fox and Singing Woman’s two boys ran alongside their mother’s horse at a brisk jogging pace, each of them taking turns riding behind her, for the horse they shared had come up lame yesterday. They do this without complaint. Truly, this is the hardiest race of people I have ever known, almost like another species altogether. It was all we could do to keep up with them.

It occurs to me how much of their life is spent running from and evading others, all with what seems to be the rather modest goal of living free. In these past days with them on the trail, we, too, have come to feel like fugitives, with the inescapable recognition that virtually everyone outside our little band—the white settlers, the miners, the soldiers, and the Indians who guide them—are all mortal enemies wishing to do us harm. For all our lack of skill at communicating with them, we have in this short time come to have a sense that we, too, are members of this tribe … a strange sensation … we against the world …

We stopped just after sunset to make our night camp. It appears that Hawk has succeeded in evading the cavalry, as he has thus far evaded contact with all. Clearly, he knows this country intimately, how to hide in it and how most efficiently to travel through it. Still, he has given us a new worry.

“Don’t be surprised if one morning we find Dabble lying in a pool of his own blood,” Meggie warned as we were setting up camp. “Or more likely gone from here altogether—butchered and cooked by the Cheyenne. And we’ll never know until it’s too late that Hawk, or someone else he sent to do the job, has been here. These people move as stealthy as ghosts in the night. They can steal a whole herd of horses without hardly making a sound. We can’t say we recommend you try it again, Molly, but you caught Hawk off guard this morning, and that ain’t an easy thing to do with a lad like him. Where in the hell did you get the pistol, anyhow?”

“I took it from Seminole.”

“Damn, lass,” said Susie, shaking her head ominously, “you took his horse, his woman … and his gun. I just hope you never run into the bastard again. We don’t need to tell you he’s right crazy, that one, and if you do, he’ll gut you like a deer and eat your organs raw. It’s a damn shame you didn’t kill him while you had the chance.”

“All I had in mind at the time was getting away from him,” I said. “I am not a killer…”

“Oh? But that ain’t what we heard,” said Meggie. “Why, we thought you were in prison for that very crime?”

“All we’re tryin’ to tell you, Molly,” said Susie, “is that you may have sent Hawk off today, but he ain’t goin’ to risk his whole damned band just to spare a fooking donkey. You can’t know this but the Cheyenne teach their children not to cry from the day they are born. This they do by pinchin’ their noses shut whenever they start bawlin’. See, there are times when attacked by enemies that the women, children, and old people must hide themselves for protection in the tall grass or in the bushes outside the village. If a baby cries, its mother is required to smother the child in order to avoid giving away the others. Aye, imagine that?… having to kill one’s own infant for crying?… it goes against every mother’s instinct, don’t it? So I think you can understand of what little consequence in comparison is the life of a donkey to these people.”

“By the by, Molly,” said Meggie. “While we’re at it, me and Susie think you’re sw

eet on Hawk. We seen you moonin’ over him.”

“What? That’s nonsense.”

“Don’t be denyin’ it, lass, we seen how you look at him. And maybe he’s a little sweet on you, too … hard to say with Hawk, he’s got such a good poker face. But even if he is, don’t count on that to get you any kinda special treatment. In case you ain’t noticed, around here everything is done for the benefit and protection of the tribe. Anyone who gets in the way a’ that, whether it be a donkey or a person, can get dead real fast.”

“Believe me, I’ve noticed. And I don’t expect special treatment, nor is Hawk sweet on me. The only time he’s even looked at me on this journey was when I pointed the gun at him. And even then he just laughed.”

“Aye, there you go, lass, you just let it slip, didn’t you?” said Susie. “You wish Hawk would pay a bit more attention to you, don’tcha now?” And the two of them look at each other and laugh in twin conspiracy.

I confess that I flushed in embarrassment then, and with no ready riposte I simply walked away. Damn those Kelly girls, anyhow, poking their noses in everyone’s business. But now that they have opened the Pandora’s box of my conflicting emotions, I may as well expose here in the privacy of this journal something I have tried thus far to ignore … and to hide … obviously unsuccessfully.

After Hawk found the chaplain and me on the trail, and led us back to the group, he did not address a single word to me, did not even look at me. I wondered at first if perhaps he was angry that I had gone off on my own, until it occurred to me that I have been acutely aware for some time that Hawk has not noticed me the entire time we’ve been traveling, nor has he spoken to me since our meeting by the river in Crazy Horse’s village.

It is true what the twins say, and why I walked away from them blushing like a schoolgirl. I have come to realize, or at least finally here admit, that I wish for Hawk to notice me, at least to look at me now and again. I have myself been experiencing a certain unfamiliar longing of late, vague stirrings long dormant and buried … and this shames me deeply … Hawk has so recently lost his wife, his mother and his child, his wounds even fresher than my own. Why should I possibly expect him to pay heed to me? And how selfish such thoughts on my part are. In addition, they seem a betrayal of my own grief, my interminable mourning of my daughter. It was oddly easier for me when I was in prison, in a tiny dark cell in solitary, dead to the world, dead to all emotion, to all hope for a future, my only longing that for my own death.

Now somehow in the course of this strange adventure, at large in this big empty country, as I learn about the lives and struggles of the other women in my company, and of these people—hunted and herded onto Indian agencies like animals into a corral—I feel myself coming back to life. It was in the monstrous grip of Jules Seminole when I first became aware of this. I was afraid again, desperately afraid; I wanted to live. Could being afraid and wishing to live suggest some small faith in a future, or is it simply a basic animal instinct for survival that has returned to me? I am unable to answer this question.

All I know … and I am ashamed to write this even in the privacy of my journal … all I know is that I long to be held in the arms of this man Hawk … and I speak here not of carnal matters, although there is that, too … rather I speak of the simple notion of being loved and protected, which I have never known as an adult … Good Lord, I must now redouble my vigilance against the prying eyes of the Kellys. If ever they were to read these pages, I would die of embarrassment.

There … I have unburdened myself of such thoughts, and perhaps in having done so, I can now put them behind me.

1 May 1876

We have reached the Tongue River, but due to our many detours and delays, we are far to the south of what seemed to be our initial general direction. The Kellys now say that in addition to evasive tactics, the long and circuitous route of travel Hawk has led us on these past weeks has been undertaken in order to cover as much ground as possible in the hope of cutting Little Wolf’s trail. In addition to being a superb tracker, because Hawk grew up in his band, he knows all the chief’s traditional campsites and hunting grounds. Thus, as well as looking out for potential enemies, Hawk and his scouts are seeking signs of their own people. To all of us unfamiliar as we are with this vast land, there is an unimaginable amount of country to cover, and it seems virtually impossible that we should ever locate them. What then, we wonder? Are we fated to wander these plains indefinitely? Yet we remind ourselves that as a boy Hawk found his people’s village after walking over a thousand miles from Minnesota. And so we keep our faith in him … what else is there to do?

We have all been making an increasing effort to ride with the Cheyenne women during the day whenever possible, and in addition to my little Mouse, I have begun to form a particular friendship with the Arapaho girl, Pretty Nose, with whom I frequently ride when she is not on scouting duty. She speaks rather good English and French, for she tells me that her father was a French trader, who spoke both languages, and between the two we are able to communicate quite well. She herself married a Cheyenne boy, and they spent time living with both tribes. They happened to be camped for the winter with Little Wolf’s band when the Mackenzie massacre occurred, and since then she’s been riding with the Cheyenne. She is a lovely young woman with a broad face, high cheekbones, clear brown skin, almond eyes, and full lips, and, as her name suggests, a particularly finely shaped nose, as if chiseled by a master sculptor. Yet for all her natural beauty, somehow, together, her features create an oddly mournful expression … a kind of melancholy, a weariness, as if she bears some deep burden. She has not spoken of it, and so I finally asked Meggie and Susie about her. They say that when the soldiers attacked that morning, rather than running from the village with most of the other women and children, Pretty Nose took up arms, killing several of the enemy and valiantly providing cover for those fleeing, saving a number of lives in the process. So furiously and effectively did she fight, it is now believed by both tribes that she has special powers in the making of war. And thus she owns the exceptionally rare status as a woman war chief.

“And she had not fought before?” I asked Meggie and Susie.

“Never,” they answered together.

“But how do you explain that? How did she even know what to do? Where did she get weapons?”

“Me and Susie did not witness her actions,” said Meggie. “But after the battle was over, she made the trek over the mountains with Little Wolf and the rest of us survivors. The way we heard it told was that her three-year-old daughter and her husband were killed in the first charge of the troops. See, Gertie told us the Army has figured out that dawn is the best time to attack an Indian village, for the people are still asleep. The soldiers are instructed to shoot low into the tipis to kill them in their beds. That is what happened to Pretty Nose’s husband and daughter, dead before they even got up for the day …

“We heard she took her husband’s tomahawk and ran outside, full of grief and rage. As one of the soldiers was riding by, she swung up behind him on his horse with a cry, they say, that would freeze your blood. She split his skull with the tomahawk, pushed him out of the saddle, reined up, slipped off the horse, collected the soldier’s pistol where he had dropped it, slid his sword outta the sheath, and remounted. The soldier’s rifle was still in the scabbard attached to the saddle. So now she was mounted and fully armed, and the rest of the morning they say she fought with the crazed power of a wife and mother’s vengeance.”

“Aye, Molly,” said Susie, “that is the mournful expression you recognize in Pretty Nose’s face … and the burden she bears…”

4 May 1876

We have had three days of rain and cold, and traveling has been miserable, our soggy evening encampments only slightly less so. However, we can hardly complain too much as we are fortunate to have enjoyed mild spring weather these past weeks. We woke this morning to clear skies again, but colder as always after the clouds lift during the night.

I write these brief words by the fire of our evening camp on the Tongue River, at the end of a very trying day. Now we know yet another reason Hawk has led us so far south. This afternoon we arrived at the scene of the Army’s February attack upon Little Wolf’s winter encampment. He had not forewarned Meggie and Susie of this return, and they were unaware of it until we actually approached the burnt-out village and the Cheyenne women took up a mournful primordial keening, heartbreaking ululations of implacable grief that seemed to speak directly to the ghosts of their dead loved ones, and brought shivers of compassion up our spines.

“Oh, sweet Jaysus, Meggie,” said Susie, her voice breaking as they both recognized the place where so many of their friends had died, and from which they had fled in terror with their babies on that frigid winter dawn. “Look where we are, Meggie … look where he’s brought us…”

“Aye, sister,” said Meggie, in a low, equally tortured voice, “full circle, right back where it all began … and all came to an end.” Now the twins themselves took up the keening, their wailings indistinguishable from those of the other women, truly their transformation to white Cheyenne complete.

La Vengeance des mères

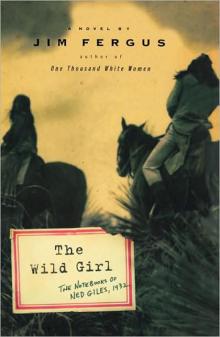

La Vengeance des mères The Wild Girl: The Notebooks of Ned Giles, 1932

The Wild Girl: The Notebooks of Ned Giles, 1932 One Thousand White Women

One Thousand White Women One Thousand White Women: The Journals of May Dodd

One Thousand White Women: The Journals of May Dodd Chrysis

Chrysis Strongheart: The Lost Journals of May Dodd and Molly McGill

Strongheart: The Lost Journals of May Dodd and Molly McGill The Vengeance of Mothers

The Vengeance of Mothers The Wild Girl

The Wild Girl