- Home

- Jim Fergus

The Vengeance of Mothers Page 12

The Vengeance of Mothers Read online

Page 12

“Is she drugged? Is that why she stares like that? Does she speak?”

“She is terribly shy with strangers,” he said. “She speaks only to Jules … ah, oui, at night she whispers tender endearments to Jules, ‘please, please,’ she says, ‘please don’t do that, please don’t hurt me anymore,’ and she weeps, the poor thing … she begs and she weeps … ah, oui, you see, she knows exactly how to excite Jules’s darkest passions.”

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw the chaplain peer over a boulder on the bluff above us, and in the same moment, Seminole, too, must have caught the flash of motion for he quickly slipped off his horse and took Spring’s halter roughly in hand. She whinnied, threw her head, and sidestepped, but he held her firm. “Dismount,” he said. “Now.” Before I had a chance, he grasped my arm and dragged me off her back. He was very strong and he pulled me close so that our faces were inches apart. I felt I was going to vomit from the foulness of his odor, his breath like a cesspool. “I believed you were all alone, ma petite. You have lied to Jules … Jules is so disappointed … Jules does not like his women to lie to him.”

“You said I was alone,” I answered. “I never said so.”

“But you did not correct me, ma petite. You see, that is the same thing as a lie.” Seminole drew his Army revolver with one hand and pulled me tight against him with the other. He pressed the barrel against my temple. “Whoever is up there,” he called, “show yourself now or this lovely girl dies.” He kissed me hard on the lips, the bile rising in my throat. I gagged, I could feel his manhood pressing against my leg. “Jules likes dead girls,” he whispered. “Sometimes they continue to twitch a little after death, but they do not struggle so much as the living.”

Now the chaplain called from the bluff: “Please, don’t harm her! I’m coming down!” He scrambled over the rocks, his saddlebags, to which were strapped a rolled Army blanket, slung over his shoulder. Seminole released me. Unable to prevent myself from it, I bent over at the waist and vomited.

“Mais, mais, is it really you?” Seminole said as the chaplain reached us. “Good Chaplain Goodman? Truly is this Jules’s most lucky day ever? Another beautiful woman has fallen under his spell … oui, ma belle, fear not, your romantic dreams will soon come true. Jules shall take you as his second bride … we, the three of us together, shall share many nights of love ahead … and … and at the same time, I have captured a notorious deserter! Jules shall be so well rewarded by mon général … perhaps … dare he hope? Perhaps Jules shall even be awarded another stripe and a medal of honor for distinguished service. Yes, Lieutenant Jules Seminole, I shall become.”

“Sergeant Seminole,” said the chaplain, “please, in the name of God, let us pretend that this encounter between us never took place. We mean you no harm. Let us go our way in peace, I beg of you.”

“Ah, but my dear Chaplain Goodman, you know perfectly well that Jules cannot do that. You are a coward who deserted your post in battle, and it is my duty to bring you to justice. I am sorry to tell you, but you will surely be court-martialed and executed by firing squad.”

At that moment, we heard the startling shriek of a hawk directly overhead, and as Seminole looked up, I reflexively performed the one effective act I had learned to neutralize my late drunken husband when he began to beat me: I kicked Seminole between the legs with all my strength, a direct hit. He groaned loudly and went down, doubled up in agony and temporarily incapacitated. I snatched his pistol from the ground where he had dropped it, and to the chaplain I hollered, “Take his horse!” As he swung onto its back, I scooped up the lead rope of the Indian girl’s donkey. Although the girl still stared straight ahead, seemingly oblivious to all that was happening around her, I could not leave her here with this wretch. I leapt onto Spring and kicked her into a run. Again there came the shriek of the hawk that seemed to issue from above and ahead of us now as we raced for the river, the donkey’s little legs working as fast as they could to keep up with the horses. I glanced behind me to make certain that the girl had not fallen off in her stupor, but now she had wrapped her arms around the donkey’s neck, holding on for life, wearing an entirely different expression on her painted face, one of utter intensity, as if she had suddenly awakened and was aware that she was escaping. We could hear Seminole cursing loudly, shouting at us to stop … I need not repeat in writing what filth he spoke.

Crossing the river, we quickly regained our night camp and found it abandoned; our party had moved out as the Kellys told us it would. How far ahead they might be and in what direction exactly, I did not know, or have time to consider, I simply rode at as fast a gallop as I was able to while holding on to the donkey’s lead rope and still allowing it to keep up. The little beast ran remarkably swiftly, as if intent himself on escaping Seminole. The chaplain rode on my other side and slightly behind me.

We rode and we rode, seeking the path of least resistance, following game trails and the natural contours of the land, keeping as much as possible to the coulees, draws, and creek bottoms, trying to put us as much distance behind as possible from that creature. We rode … we rode … I do not know for how long, until finally it occurred to me that I was lost. I reined up, and so did the chaplain.

“Do you know where we are?”

He looked at the sun, still quite low in the morning sky. “Roughly.”

“Yes, but do you know where we’re going? Do you have any idea how we can find our party?”

“Back at the river, we might have picked up their trail.”

“But we did not.”

“We did not. We had no time to look for it. I simply followed you.”

“So then we are lost.”

“Perhaps a little…”

“You cannot be a little lost,” I said. “Either you are or you aren’t.”

“My sense is,” he said, “that if from here we strike roughly the same trajectory your group has been moving these past days, we should perhaps come upon them. You must know at least what direction you’ve been traveling?”

“Roughly west and slightly northward,” I answered, “with many detours. Meggie and Susie told us we were heading toward the Tongue River.” I pointed vaguely to the faint outline of the Bighorn mountains on the distant horizon. “That way.”

“A good beginning,” said the chaplain, “although there is a great deal of country between here and there.”

“And what do you propose we do now?”

“I suggest we continue on, and we trust in God to lead us on the right path.”

“I don’t believe in God.”

“Yes, but I do.”

On we rode, mostly walking the horses now, occasionally breaking into a brief trot, traveling west and north, not knowing where we were headed other than the general direction, or if we would ever find our people, not knowing if anyone was following us. We assumed that Seminole must have been with the party of white men our scouts had discovered camping upriver. We took some small comfort in knowing that, at least for a time, he was afoot, though we had no idea how far away from them he had been when he came upon us.

All day we rode like that, stopping only to water and rest the horses. We had no food or supplies and we did not stop to hunt. I came quickly to believe that we were going to perish out here, and it rather surprised me to recognize that I no longer wished to die.

The painted girl, as I came to think of her, had resumed her trancelike state. She sat steady on her donkey’s back, but she did not speak or react to us when we tried to address her. Nor did we know if she even understood our language. I could only imagine what degradation and perversity she must have endured at that man’s hands, and I understood that the only means for her to survive the ordeal must have been to retreat to some untouchable, unreachable place. I had seen women in prison, victims of violation and beatings, accomplish this sort of disappearance, becoming like phantoms … I had nearly done so myself …

On we rode, feeling so tiny, so helpless, so hopeless in the task of findi

ng our people in the vast rolling sea of this big, empty country.

We stopped for the night beside a small creek. We had nothing to eat, but in his saddlebags the chaplain carried a length of fishing line and a hook. He cut a green willow branch and tied the line to the end of it, dug worms in the soft dark soil of the creek bank to use as bait, and with this makeshift rig quickly caught a half-dozen trout. I have to admit he is a resourceful fellow, this chaplain, with a great deal of energy. We allowed ourselves a small fire, and roasted the fish impaled on willow sticks. The chaplain also had a little bag of salt in his bag, which he removed as reverently as if it were a sacred object. “All this time,” he said, “I have only used a tiny pinch now and again on special occasions so that it would last. I am so grateful now to share this with you.”

“What kind of special occasions did you have alone in your cave?” I asked.

“Well … modest ones, to be sure … for instance, if I happened to acquire a little fresh meat … something other, of course, than rodentia.”

The painted girl ate her trout hungrily. She clearly still possessed an instinct for survival. We had only the one Army blanket for the three of us, and when the evening air grew cool, I draped it across her shoulders. Our sleeping arrangements seemed at first a bit complicated. On the one hand, we needed to share body warmth; on the other we had discovered over the course of the day that the girl had an understandable aversion to being touched, particularly by the chaplain. Thus we made a bed of dried grass, and he took his place on the outside, I in the middle, and the girl beside me. She tried at first not to have any contact with me, which only resulted in her lying outside the blanket. Yet she fell asleep quickly, and when she was breathing steadily, I took her gently in my arms, pulled her toward me, and covered her again. In the course of the night, I think she took some small comfort in lying against me, some solace in a woman’s soft embrace that perhaps recalled the safety of infancy when she lay in her mother’s arms … indeed, the embrace brought back painful maternal memories of my own. She was such a skinny little thing, I could feel her bones poking into me. I felt that I needed to protect this girl, whoever she was … as I had failed to protect my daughter.

As if from a dream, we were awakened abruptly at first light by the cry of a raptor overhead. I lay on my back and looked up to see the bird, wings set, circling high above. At that moment, we heard the hoofbeats and rustling brush of an approaching horse, and fearing the worst the chaplain and I scrambled to our feet. As we did so, the girl, too, sensing danger, sat up, and crabbed backward in a kind of panic. It was then that the Cheyenne warrior, Hawk himself, rode into our bivouac. The chaplain, not recognizing him, not knowing whether he was from a hostile or friendly tribe, said: “Welcome, friend! Welcome to our humble camp!”

“Do not be afraid, Christian,” I said. “This man is with us … or I should say, we are with him. Or at least, we are supposed to be.”

“But I am not afraid,” said he. “I am always joyful to receive a visitor! It is a tradition of my faith. Please, sir, allow me to build a small fire to warm you, and catch a trout or two to cook for your breakfast. God provides us with his bounty. And … and I have salt!”

“You came back for us, Hawk,” I said, gratefully.

He did not answer, or even look at me, as is his way. He dismounted and approached the girl, squatting down beside her. He looked closely at her, then spoke to her in Cheyenne. She did not respond, but her eyes focused upon him. He nodded, placed the fingers of his right hand lightly against her cheek, and spoke to her again. I had the distinct impression that they knew each other.

The chaplain scurried about, gathering sticks and rebuilding the fire, blowing gently on the few embers that still glowed beneath the ashes, finally coaxing a small flame to life, to which he held thin strips of dry willow bark until they flared. When he had a decent fire burning, he went down to the creek with his fishing pole and proceeded to quickly catch another mess of fat trout, which he cleaned with his knife.

We ate our trout, and as there was little to pack beside the chaplain’s blanket, we were mounted and ready to move out just as the sun was cresting the hills to the east. Having ascertained that I no longer needed to lead the donkey, I had tied his halter rope around his neck, and he followed along in his cheerful trotting gait, ears alertly pricked forward.

After the previous day’s sense of helplessness at being lost wanderers, I felt such peace in being again under Hawk’s wing, as I believe did the chaplain, who, giving full credit to his God for the man’s appearance, chattered on gaily to the three of us as we rode. After all that time alone in his cave, it seemed he had stored up an inexhaustible torrent of words, which he now released upon us. It did not seem to bother him in the least that I was the only one who responded, and even then, only occasionally.

It was late afternoon before we finally caught up with our band, who had already made their evening camp. All the girls were so relieved to see us, and we them, there was much hugging and shedding of tears … with the exception of the Kelly girls’ welcome. “What the fook were ya doing back there, Molly?” Meggie asked angrily. “And who the hell is this ya bring with ya?”

“We were detained by your charming friend, Jules Seminole,” I answered. “I have no idea who the girl is. He said she was his wife. I brought her with us when we escaped because it was clear that she was not with him of her own free will. As you can see for yourselves, she is terribly damaged.”

“Seminole? Holy Jaysus…” the twins said in unison. “I’ll wager, he’s guiding the party of white men, ain’t he?” said Susie.

“I don’t know about that. He was alone with the girl when he came upon us.”

“Aye, they’ll be after us for sure now,” said Meggie. “You’d a’ done better to leave her with him.”

“The chaplain took his horse,” I said, “so at least he was on foot for a time.”

“How in the hell did you get away from him, and with his wife and horse to boot?”

“There was a distraction of sorts … a hawk scream overhead … When Seminole glanced up, I kicked him hard in the … in the bollocks as you put it … and we managed to escape.”

“You’ve brought danger down upon us all, Molly,” said Susie. “Hawk left us to find you, and we could have lost him, too.”

“But you did not,” I pointed out.

“And now you’ve kidnapped Seminole’s wife,” said Meggie. “We know this man … there will be hell to pay, believe us. He will hunt us down to take back what is his.”

“I did not kidnap her,” I said. “I liberated her from that monster. Yes, perhaps it was foolish of me to go off like that. I’m sorry. But Seminole will have to catch us first, and I believe Hawk will evade him, and protect us, as he has thus far.”

“Just so you know,” said Meggie, “me and Susie talked about it, and we decided that even if you made it back, which we were beginnin’ to doubt … we decided Lady Hall should be the new leader of your group. We believe she is a wee bit steadier than you, a wee bit less rash.”

“That is just fine with me, girls. I agree with you. I do not wish to be the leader any longer. You’re quite right, I am not fit for the job.”

“Rubbish!” said Lady Hall. “I won’t hear of it. I say that Miss Molly has performed a rather brave and admirable service. She saved the chaplain from what could only have been an unpleasant end, and—”

“Yes, Seminole was going to turn me over to the Army,” Christian interrupted her. “He said I would be court-martialed for desertion, and executed by firing squad. Molly saved my life.”

“… and she rescued this poor girl,” continued Lady Hall, “from the clutches of that unsavory fellow. I say, to quote the great Shakespeare, that all’s well that ends well.”

Meggie now walked up to the painted girl, who still sat her donkey and had fallen again into her trancelike state. “Susie, come over here,” she said, peering at the girl curiously. “Bring your canteen and

a piece of cloth.”

When Susie came to her, Meggie began wiping the red clay greasepaint from the girl’s face. “Aye, look, it’s just as I thought,” she said, “she’s not a savage at all, she’s a white girl beneath all of this.”

“Aye, and she stinks, too, don’t she?” said Susie. “The mud must be mixed in bear fat. Nothing stinks worse than fooking bear fat.”

Meggie poured more water on her rag and continued scrubbing the girl’s face. Suddenly she stopped and stared hard at her. “Holy … mother … of Jaysus,” she whispered under her breath. “Do you see what I see, sister?”

“Aye, Meggie,” Susie whispered back. “I do … I do … I see…”

“But it ain’t possible, it cannot be,” said Meggie. “Is that you? Is it really you?” The girl did not answer or react in any way, she just stared straight ahead, one side of her face half-cleaned. Meggie shook her violently, then dragged her off the donkey’s back to her feet, and shook her again. “Wake up, lass, wake up now, speak to us.” Still no reaction. Finally Meggie hollered: “Goddammit all, is that you, Martha, is it really you?” And she slapped the girl hard across the face. “Wake up, goddamn you!” Now the girl seemed to struggle into consciousness, her eyes coming into focus. She looked back and forth between Meggie and Susie. “Don’t hurt me,” she said in a tiny, wounded, pathetic voice, “please, please don’t hurt me anymore,” and she began to weep.

“Oh Jaysus, Martha,” whimpered Susie, the twins now weeping as well. “Jaysus Christ.” Together they embraced the girl, the three of them bawling in each other’s arms. “No, no, Martha, please don’t cry,” said Meggie through her tears, “we won’t hurt you, no one will hurt you, dear Martha, we’ll take care of you … you are home … aye, don’t you see, you are home with us, you are safe now.”

25 April 1876

No time to make entries these past days … We have been traveling with greater haste since the encounter with Jules Seminole, departing at dawn without making fires, eating only strips of dried buffalo meat, and what roots and meager greens, mostly dandelion leaves, we are able to gather in the creek bottoms. Only after several days of this, when the scouts were unable to find any evidence that we are being followed, and no further sign of the party of white men, has Hawk permitted small fires to be built again—but only long enough to cook and take some brief warmth before being quickly extinguished.

La Vengeance des mères

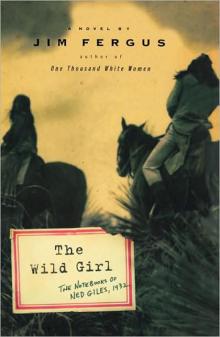

La Vengeance des mères The Wild Girl: The Notebooks of Ned Giles, 1932

The Wild Girl: The Notebooks of Ned Giles, 1932 One Thousand White Women

One Thousand White Women One Thousand White Women: The Journals of May Dodd

One Thousand White Women: The Journals of May Dodd Chrysis

Chrysis Strongheart: The Lost Journals of May Dodd and Molly McGill

Strongheart: The Lost Journals of May Dodd and Molly McGill The Vengeance of Mothers

The Vengeance of Mothers The Wild Girl

The Wild Girl